SNaP Chapter 1: Kindergarten Rules

Leadoff chapter for second edition of the

Sacred Nonaggression Principle

In case you missed the first cut on the next edition—posted as an article, Space Lizards and Pod People a couple of months ago—here's the latest Chapter One. I have not given up on the SNaP; in fact I'm more convinced than ever it represents the spiritual salvation of the species. Please help me make the best case possible by commenting on this column by sending me an email or subscribing and commenting to the Coffee Coaster blog. Thank you.

— Brian Wright

Getting Started: Kindergarten Lessons

Some simple rules of childhood lead to big truths

Summary

Leading off with axioms[1] of proper behavior that hail from the maxims most humans learn from our earliest days: 1) Don’t hit, 2) Don’t steal, 3) Don’t lie. Let us respect, even ‘worship,’ these ideas as adults.

The above definition of aggression is fairly conventional in libertarian circles, and banning “the initiation of physical force” uses phrasing from the nonfictional writings of Ayn Rand and her supporters. It is very precise wording that leaves little room for misunderstanding as to what aggression is or is not.

Let’s Pretend We’re Five-Year-OldsRemember in the Tom Hanks’ movie Philadelphia, the attorney character played by Denzel Washington. He is investigating the conduct of Hanks’ company, the nature of the AIDS disease, and applicable law. When Denzel thinks some authority he’s questioning is being obtuse or trying to snow him, he says “Hey, pretend I’m a five-year old.” In other words, don’t beat around the bush, give me the facts in plain English a child can understand. No baloney stuff.

Conveniently, the basic idea I’m trying to convince you of in the book is something most of us learned when we were five years old: The Kindergarten Rules

What is aggression? I’ve found that the best starting point comes from a marvelous book by Mr. Robert Fulghum entitled, All I Really Need To Know I Learned in Kindergarten. The book is a collection of some of his life experiences, from which he usually distills a moral. In the principal story, he tells us that kindergarten taught him the following:

Don’t hit

Don’t steal

Be honest (don’t lie, keep promises)

Sure, there are several other related lessons Fulghum remembers from kindergarten—such as cleaning up your mess, putting things back where you find them, washing your hands, flushing, etc. But Fulghum’s Kindergarten Rules have been popularized among journalists and pundits as common-sense moral ideals.

So where did “the Rules” come from, and what makes them so special? I write from an American context, and my possibly parochial[2] judgment is that the Kindergarten Rules are a distillation, for children, of the fundamental truths embedded in the country’s founding: the Inalienable Rights of Man and equality before the law. Since it is right for every individual to take action required for life and happiness, let no one else—especially the state—wrong the individual by forcibly interfering with those actions… by aggressing upon or coercing the individual. In a child’s world, aggression or coercion are primally seen as “hitting, stealing, or lying.” Moral Tenets

Religious and secular-philosophic foundations also exist for ingraining the Rules in kids’ minds. The Abrahamic religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—all enjoin[3] stealing… whether the object of theft is a golden chalice or carnal knowledge[4] with someone else’s wife. (They also proscribe killing, unless God gives you the green light to snuff out a nonbeliever.)

All great systems of moral thought require as a minimum that you follow the Golden Rule (at least among your own people). Accordingly, the formal, enforceable rules of conduct—i.e. laws—in every civil society are based on each individual at least being able to keep his stuff from being ripped off by the force or fraud of other individuals. Then—as we proceed thru the Enlightenment’s concept of liberty—monarchs, oligarchs,[5] and governments are also restricted from taking your things or infringing on the peaceful being of you.

The latter paragraph expresses reasons for practicing the adult principle—the nonaggression principle—but it’s easy to see how these reasons apply on the playground: “Johnny,” the teacher says, “I think you can see by not starting the use of force (that is, hitting Joey, taking lunch money from Sam, or turning in Lisa’s homework as your own) your world becomes better. Not only do you escape punishment from me; other children will give you the same respect you give them.” [Granted, the communication of this truth is seldom accomplished, for a child of that age, in such a conceptual statement, rather by perceptual methods via nods, frowns, and so on.]

Core Values

Closely related to the moral premises[6] of civil societies that disallow aggression—premises that the Kindergarten Rules engender—are the “sacred” values that all good citizens in a given society intuitively understand and accept. In the United States today there’s even a “Core Values” movement, but let’s just pick some of the standard phrases that we regard as key American values:

- Rule of law

- Equality of rights

- Life, liberty, and property

- Popular sovereignty

- Separation of powers

- Sanctity of family

- Home as a castle

- Justice is impartial

- No legal privileges

- Respect for (valid) authority

- Honoring our (wise, moral) elders

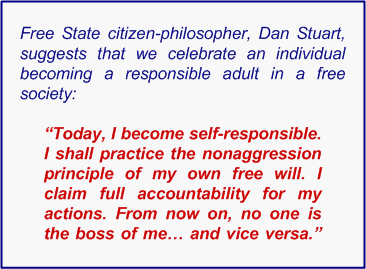

And so on. The logical path from the behavioral axioms of childhood, the Kindergarten Rules, leads thru religious tenets and core values to the prescription for the Big Universal Problem (BUP)… that we spoke of, before. That prescription (cure) for the BUP is, indeed, the simple nonaggression principle. Growing Up to the Nonaggression RuleAs we put away childish things, and if we’ve largely abided by the Kindergarten Rules as we grow up, then the adoption of the nonaggression principle as adults becomes second nature to us.

As an all-American thought experiment, please consider, out of all the people you’ve met in your adult life from every social station, how many would steal directly from another human being… or beat them or defraud them: How many? One in a hundred? One in a thousand? My experience is fewer than one in a thousand… certainly when one considers the actual act of stealing something. [The ratio may approach one in ten, if we’re talking about trying to get the best deal in a barter, for example, by not being fully candid. But even there, my experience is 9 out of 10 adopt the ‘open kimono’ policy when making a deal.] The point is—whether the number of persons is 1/100 or 1/1000—darned few of us believe in or practice one-on-one, human-to-human aggression. Moreover, the average person absolutely detests anyone who would intentionally commit the smallest act of assault, theft, or dishonesty. Thus, as Americans, as a consequence of the Kindergarten Rules, then later as we embrace—through moral tenets and core values—those rules more conceptually in the form of the nonaggression principle, we overwhelmingly will not directly initiate force against another. I repeat, 99.9% of Americans, one on one, will not aggress upon another and despise the 0.1% who would. Not Under Any Circumstances

Let’s return to kindergarten and recall that a key element in the teaching of the Rules was “no wiggle room.” In other words, Johnny didn’t get a special allowance to use Lisa’s homework on only one particularly difficult problem… or ½ a problem or ¼ a problem. Or let’s say he “meant well” and his parents assert convincingly that the community will be wondrously benefited by Johnny receiving an A on his report card. Nope. Under the Kindergarten Rules, such shading, quibbling, and evasion don’t cut the mustard. Life is simple, Sherlock, don’t aggress. The idea of “no exceptions” is closely tied to the adult practice of the nonaggression principle, too. In our thought experiment, do you think any of the 999 people care one whit that someone’s sad childhood gives him a craving to hurt others. Not at all; we all have to play by the same rules. So long as you wish to remain in society, the nonaggression principle is an absolute. Indeed, a willingness to abide by the nonaggression principle is the condition a society typically applies to the right of enjoying freedom. No Privileged OnesI remember once in fifth grade when the teacher accosted me for disrupting the class, I pointed to my partner in disruption and said, “What about Suzy? She started it!” I admit it’s not a great example; I was basically ratting out my friend… and a girl at that. What a wimp! [Plus it didn’t turn out well: the teacher was a reform-school psycho who grabbed me by my shirtfront and threw me out the door like a shuffleboard weight.] The idea is nobody should be exempt from the Rules simply because he’s a teacher’s pet or—in Grownupville—because he/she provides special personal services for a policeman, prosecutor, judge, or politician. More broadly, consistent with the country’s founding, no “titles of nobility” shall be granted… one group cannot subordinate another group.

Legal equality = core value.

QED[7]We have the Kindergarten Rules (KRs) for children and the nonaggression principle (NaP) for everyone. It is straightforward to show that a) the KRs—practiced absolutely and equally—result in the best of all possible political worlds for children, and b) the NaP—practiced consistently and equally—results in the best of all possible political worlds for everyone. The remainder of the book describes how.

###

[1] An axiom is a self-evident truth that supports other truths.

[2] Parochial means local or confined to one’s own part of the larger world, it suggests narrow mindedness.

[3] To enjoin is to forbid, to prohibit.

[4] Sexual intercourse, the horizontal mambo, the Bodie-O-Doh.

[5] An oligarchy is a system where a few people rule the many.

[6] A “premise” is a beginning statement in a “proof.” For example, “We need to all get along” can be considered the premise the argument that, “It is best that I not club Larry over the head with a baseball bat.”

[7] Abbreviation for quod erat demonstrandum, Latin for “which was to be demonstrated (proved).”

2009 November 16

Copyright © Brian Wright | The Coffee Coaster™

Sacred Nonaggression Principle | Liberty | Core Values | Kindergarten Rules

|