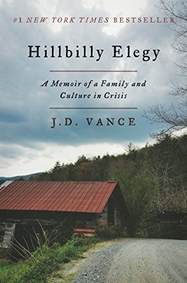

Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis

By JD Vance, reviewed by Brian R. Wright

The reviews of Hillbilly Elegy have been almost universally positive, expressing an appreciation in particular of “the real people who are kept out of sight by academic abstractions” (per Peter Thiel, author of Zero to One). We are speaking of the southeastern US ‘hillbillies,’ who come from Scots-Irish stock and are a major political-social grouping in America. Mr. Vance gives us a mem- orable down to earth rendering of a culture that is certainly relegated by the elites of the political class into facts and figures. He gives us a bird’s eye view, a gonzo journalistic, ‘you are there,’ day by day account of his own days of growing up from his Kentucky homeland and southern Ohio.

The reviews of Hillbilly Elegy have been almost universally positive, expressing an appreciation in particular of “the real people who are kept out of sight by academic abstractions” (per Peter Thiel, author of Zero to One). We are speaking of the southeastern US ‘hillbillies,’ who come from Scots-Irish stock and are a major political-social grouping in America. Mr. Vance gives us a mem- orable down to earth rendering of a culture that is certainly relegated by the elites of the political class into facts and figures. He gives us a bird’s eye view, a gonzo journalistic, ‘you are there,’ day by day account of his own days of growing up from his Kentucky homeland and southern Ohio.

From the front jacket: Hillbilly Elegy is a passionate and personal analysis of a culture in crisis—that of poor, white [mainly, Appalachian—ed.] Americans. The disintegration of this group, a process that has been slowly occurring now for over 40 years, has been reported with growing frequency and alarm, but has never been written about as searingly from the inside. In Hillbilly Elegy, JD Vance tells the true story of what a social, regional, and class decline feels like when you were born with it hanging around your neck.

Myself hailing from middle-class Overland Park, Kansas, then mainly the Detroit, Michigan, suburbs as I reached my 20s, I have known many people who ‘came from the south,’ to work in the automotive world and the more industrialized north. In fact, one of the people I most respect in the world was my first real boss, in the mid-1970s aerospace, Jim Cline, hailing from good ol’ boy Hickory, North Carolina. I can hear the drawl now. Vance writes of his kin:

My grandparents were part of the second wave, composed of returning veterans and the rapidly rising number of young adults in 1940s and 1950s Appalachia. As the economies of Kentucky and West Virginia lagged behind those of their neighbors, the mountains had only two products that the industrial economies of the North needed: coal and hill people. And Appalachia exported a lot of both.

— pg. 28

Like Vance (Marine corps, Yale Law, well-to-do and happily employed), Jim truly made something of himself (engineer, business owner, millionaire). I’ll add that what distinguishes both men is they are superb leaders of men. The question raised by the book is how is it that people such as Jim and JD rise while so many of their kin fail? Candidly, I’ve tended to answer that question, when it’s posed in a group setting, quite facilely: it’s free will, by golly. Which really only pushes back the question further: “Okay, well why do those who choose to rise come to entertain the choice?”[1]

Vance does a fair job of keeping his own freedom of choice intact while resolving to my satisfaction the role of environment: his grandma, in particular, Mamaw. Without her caring about him at a young age—Mamaw and Papaw were effectively his parents, as his mother was let’s just say morally weak— JD believes he would have had no chance.

Interesting to me is that the same sort of family dynamic that we witness with poor urban blacks, where the men abandon their progeny and the women too often become irresponsible ‘welfare mothers,’ is a common phenomenon in poor rural white societies. Thus, if you can figure out how to solve the problems of one, you can do the other, as well. [My own thoughts and feelings, these days, are that the prevailing philosophies of society have to be supplanted with a better one(s)… and my Trumanism is a good candidate, especially when grounded in reasoned spirituality.]

But I’m sliding away from the review. The thing about JD Vance is he’s extremely human and down to earth, and brutally, often humorously so, honest. Like my former boss, Jim, JD will forever ‘love his people to the utmost.’ JD writes wonderfully. I’m sure the editors over there at HarperCollins can be credited with some of that manifestation, but you really feel what he’s feeling or what he went through, without any pretense. He’s just who he is and it’s pretty impressive when you hear the story of his surroundings growing up.

It’s a colorful tale, and I especially like Mamaw’s frank, profane manner:

“Bob Hamel, my stepdad and eventual adoptive father, was a good guy in that he treated Lindsay and me kindly. Mamaw didn’t care much for him, ‘He’s a toothless fucking retard,’ she’d tell Mom, I suspect for reasons of class and culture: Mamaw had done everything in her power to be better than the circumstances of her birth…. Bob, however, was a walking hillbilly stereotype.” — pg. 62

“I broached this issue [of concern about his manhood] with Mamaw, confessing that I was gay and I was worried that I would burn in hell. She said, ‘Don’t be a fucking idiot, how would you know you’re gay?’ I explained my thought process…. Finally she asked, ‘JD, do you want to suck dicks?’ I was flabbergasted. Why would someone want to do that? She repeated herself, and I said, ‘Of course not!’ ‘Then,’ she said, ‘you’re not gay. And even if you did want to suck dicks, that would be okay. God would still love you.; That settled the matter…. There were more important things for a Christian to worry about.” — pg. 98

Other splendid observations about the way things are in that neck of the woods:

“Today downtown Middletown is little more than a relic of American industrial glory. Abandoned shops with broken windows line the heart of downtown, where Central Avenue and Main Street meet. Richie’s pawnshop has long since closed, though a hideous yellow and green sign still marks the site, so far as I know. Richie’s isn’t far from an old pharmacy that, in its heyday, had a soda bar and served root beer floats. Across the street is a building that looks like a theater, with one of those giant triangular signs that reads ‘ST____L’ because the letters in the middle were shattered and never replaced. If you need a payday lender or a cash-for-gold store, downtown Middletown is the place to be.” — pg. 50

The author is not easily snowed…

“[Attitudes are reflected…] less in what people say than in how they act. One of our neighbors was a lifetime welfare recipient, but in between asking my grandmother to borrow her car or offering to trade food stamps for cash at a premium, she’d blather on about the importance of industriousness. ‘So many people abuse the system, it’s impossible for the hardworking people to get the help they need,’ she’d say. This was the construct she’d built in her head: Most of the beneficiaries of the system were extravagant moochers, but she—despite never having worked a day in her life—was an obvious exception.” — pg. 57

“I don’t believe in epiphanies. I don’t believe in transformative moments, as transformation is harder than a moment. I’ve seen far too many people awash in a genuine desire to change only to lose their mettle when they realized just how difficult change actually is.” — pg. 173

I like Vance’s balanced appreciation of others’ religious beliefs or nonbeliefs:

“Dad’s church offered something desperately needed by people like me. For alcoholics, it gave them a community of support and a sense that they weren’t fighting addiction alone. For expectant mothers, it offered a free home with job training and parenting classes. When someone needed a job, church friends could either provide one or make introductions. When Dad faced financial troubles, his church banded together and purchased a used car for the family. In the broken world I saw around me—and the people struggling in that world—religion offered tangible assistance to keep the faithful on track.” — pg. 94

His wry sense of humor, again and again:

“So I wondered what was different about us—not just me and my family but our neighborhood and our town and everyone from Jackson [Kentucky] and Middletown [Ohio] and beyond. When Mom was arrested a couple of years earlier, the neighborhood’s porches and front yards filled with spectators; there’s no embarrassment like waving to the neighbors right after the cops have carried your mother off. Mom’s exploits were undoubtedly extreme, but all of us had seen the show before with different neighbors. These sorts of things had their own rhythm….” — pg. 140

And expressing his view of the political upshot of what he’s learned:

“Political scientists have spend millions of words trying to explain how Appalachia and the South went from staunchly Democratic to staunchly Republican in less than a generation. Some blame race relations and the Democratic Party’s embrace of the civil rights movement. Others cite religious faith and the hold that social conservatism has on evangelicals in that region. A big part of the explanation lies in the fact that many in the white working class saw precisely what I did, working at Dillman’s. As far back as the 1970s, the white working class began to turn to Richard Nixon because of a perception that, as one man put it, government was ‘payin’ people who are on welfare today doin’ nothin’! They’re laughin’ at our society! And we’re all hardworkin’ people and we’re gettin’ laughed at for workin’ every day!’ — pg. 140

“People sometimes ask whether I think there’s anything we can do to ‘solve’ the problems of my community. I know what they’re looking for: a magical public policy or an innovative government program. But these problems of family, faith, and culture aren’t like a Rubik’s Cube, and I don’t think that solutions (as most understand the term) really exist. A good friend, who worked for a time in the White House and cares deeply about the plight of the working class, once told me, ‘The best way to look at this might be to recognize that you probably can’t fix these things. They’ll always be around. But maybe you can put your thumb on the scale a little for the people at the margins.'” — pg. 238

Hillbilly Elegy for me is a pleasant, informative stroll through a world that I didn’t realize was so effed up. Which may not show much sensitivity on my part, but I think it’s the tack Vance wants us to take: to be sympathetic but not try to put lipstick on a pig. I like the writing and the good nature of the author, and appreciate the better—by no means exemplary—characters he shares with us, such as Mamaw and Papaw, his sister, his real father, and so on. I also appreciate many of the majorly flawed ones; I’ve known a few, myself, in my day, and still love ’em.

Another book I reviewed, written in the George Bush II era, Deer Hunting with Jesus, takes on the subject of the Scots-Irish from the hills of the South more en masse and explicitly politically. I also enjoyed it and would recommend its slightly different angle of illumination, still with the affection Mr. Vance accords his people. I do have to state that my sense of the overwhelming popularity of Hillbilly Elegy in elite circles comes off much overblown or not truly connective. But at least they show signs of feeling the drought of authenticity in our general culture and wanting to feel something genuine.

[1] Ayn Rand, my first major philosophical teacher, argued that free will is a prime mover in consciousness, but the prime moving aspect of free will is that the being is choosing to raise his mental focus… rather than blank out. In Vance’s case, and in my former boss Jim’s case, they had chosen to be aware enough to see a thread through the maze —either via people or circumstance. Then once that awareness leads to better choices, better choices have their own built-in incentives to carry on and get even more value. Until then you’ve created yourself as a remarkable, heroic standup human being of pride and confidence.

This post has been read 1312 times!