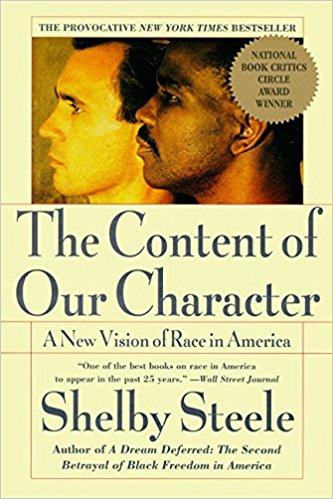

A new vision of race in America (1990)

by Shelby Steele

Reviewed by Brian R. Wright

Reposted for timeliness… from my original review in September 2012. — bw

Reposted for timeliness… from my original review in September 2012. — bw

“Moral power precludes racial power by denouncing race as a means to power. Now suddenly the [black power] movement itself was using race as a means to power and thereby affirming that very union of race and power it was born to redress. In the end, black power can claim no higher moral standing than white power.”

— Page 19

Shelby Steele’s unique book, The Content of our Character, arose from various essays he had written for such prestigious publications as Harper’s, New York Times Magazine, Commentary, the Washington Post, and American Scholar. Character is essentially an anthology of these groundbreaking articles, and argues a central thesis more or less condensed in the above quotation from page 19. It is remarkable that Steele’s stimulating and controversial book was published nearly two decades ago… and that few black intellectuals of stature— including Steele himself—have built on his startlingly ameliorative infrastructure of ideas.

What happened? Why did the intelligentsia—black, white, or magenta—drop the ball so glaringly? It’s as if Michael Jordan, through superhuman athleticism, scored 30 points in the first quarter of a title game against the Lakers, then for the remaining three quarters the whole team went to sleep. I have my own ideas, though of course I cannot speak for the motives and life situation of Dr. Steele, a professor of English at San Jose State University in California.

Here’s what I suspect: 1) If you’ll forgive the expression, Steele has been black-balled by the ‘victim-sleazeball’ coterie of Sharpton & Jackson, Inc. and 2) the Kleptocons, having a vested interest in racial disharmony and human suppression, don’t want to facilitate such a psychologically liberating worldview.[1]

Black Power vs. Black Freedom

My morning paper today carried a piece by black “conservative”[2] economist Walter Williams, who could have been writing a page out of Steele’s book. Williams was commenting on the HBO documentary, “Hard Times at Douglass High,” that aired in June 2008. It concerns the tragedy of (lack of) education in predominantly black urban government schools—by every measure these schools are failing abysmally. Why? Frederick Douglass, as Dr. Williams points out, was founded in 1883 as the Colored High and Training School, and is one of the nation’s oldest black high schools. Several eminent men and women are graduates, from Thurgood Marshall to Cab Calloway:

“Politicians and the teaching establishment [and presumably the writers of the HBO documentary] say more money, smaller classes, and newer buildings are necessary for black academic excellence. At Frederick Douglass’ founding, it didn’t have the resources available today. If blacks can achieve at a time when there was far greater poverty, gross discrimination, and fewer opportunities, what says blacks cannot achieve today?”

Walter Williams then concludes ” …the ‘welfare state’ [my quotes] has done what Jim Crow, gross discrimination, and fewer opportunities could not have. It has contributed to the breakdown of the black family structure and has helped establish a set of values alien to traditional values of high moral standards, hard work, and achievement.” Williams focuses on statist political and economic barriers to black success, while Steele points out the moral and psychological virtues that these barriers (these siren songs of renewed slavery) inhibit:

“It was the emphasis on mass action in the sixties that made the victim-focused black identity a necessity. But [today] when racial advancement will come only through a multitude of individual achievements, this form of identity inadvertently adds itself to the forces that hold us back. Hard work, education, individual initiative, stable family life, property ownership—these have always been the means by which ethnic groups have moved ahead in America. Regardless of past or present victimization, these ‘laws’ of advancement apply absolutely to black Americans also. [italics mine]” — page 108

Oddly enough—though Williams could certainly be considered a libertarian in several areas—neither scholar feels comfortable challenging the 900-lb gorilla of state coercion in either “welfare” systems or “education” systems. Both men can provide to the urban poor a big boost of psychological freedom if they would read and promote John Taylor Gatto’s arguments[3] for uncreating the school qua prison leviathan that bears down so heavily upon them. Similarly, speaking of prison, neither Williams nor Steele seem to acknowledge the craven aggression inflicted disproportionately on poor minorities via the WOD (War on Drugs)—the sole reason almost as many American black men are in jail as in college.

Well, we could go down the WOD-argument path quite a ways, but let’s just acknowledge that the instruments of oppression of minorities, particularly blacks, lie in the hands of rich, powerful, predominately white corporate-statist and socialist-statist men. Steele senses this condition, and finesses it by advocating that blacks eschew affirmative action or other forms of racial preference. The beneficiaries of racial preference are a) the sorts of individuals who are inclined to want something for nothing and b) administrators who aim to assuage guilt by seeming to care but in reality perpetuating a false and “easy” inferiority on the preferred—while stomping on the hopes of less fortunate persons aiming to better themselves through hard work and individual virtue.

“In any workplace [or schoolplace—bw], racial preference will always create a two-tiered population composed of preferreds and unpreferreds. This division makes automatic a perception of enhanced competence for the unpreferreds and of questionable competence for the preferreds—the former earned his way, even though others were given preference, while the latter made it by color as much as by competence. Racial preferences implicitly mark whites with an exaggerated superiority just as they mark blacks with an exaggerated inferiority. They not only reinforce America’s oldest racial myth but, for blacks, they have the effect of stigmatizing the already stigmatized.” — page 120

Opportunity as Responsibility

In other words, when someone says, “We’re from the government and we’re here to help you,” run. Particularly, if they want to help you, a black minority, with continued devious assertion of a false white superiority. These are not your friends. Neither are Sharpton & Jackson, Inc. who try to cash in on white guilt per black victimization (usually, indeed preferably, bogus, e.g. the Don Imus or Kelly Tilghman incidents). Blacks who achieve and who refuse false paradigms of victimhood—try making Tiger Woods or Barack Obama feel sorry for themselves—are bad for the shyster business: “If you’re not a victim, we don’t get paid.”

The book is illuminating, especially on the the psychological problem of perceived inferiority (by the minority race when obliged to work and live within a social system dominated by the majority race), something I hadn’t considered before. Steele comes to grips with this, and I can definitely feel how the reasoning lifts the souls of those facing such issues. But there’s so much more, discussion of several terms and concepts that convey key ideas that mostly help to move the philosophical and psychological liberation along: “moral power,” ” racial power,” “race holding,” “struggle for innocence,” “bargainer’s strategy,” margin of choice,” “racial vulnerability,” “compensatory grandiosity,” “politics of difference,” “memory of oppression,” etc.

I suppose the book is mainly meant for ‘blacks like me,’ i.e. black citizens who are struggling, as does Steele, with the best options for personal fulfillment… now that legal racial discrimination has ended. As a white man, I read it with great sensitivity to the universal human struggle and how best each of us can achieve his dreams. My focus for helping others has always included removing the obstacles of state coercion; Steele is a little deeper and more into the prospects of the black mind. In any case, this is a phenomenally great book and should be considered required reading by any political or literary figure. I’ll close with a particularly poetic excerpt:

“Personal responsibility is the brick and mortar of power. The responsible person knows that the quality of his life is something that he will have to make inside the limits of his fate. Some of these limits he can push back, some he cannot, but in any case the quality of his life will pretty much reflect the quality of his efforts. When this link between well-being and action is truly accepted, the result is power. With this understanding and the knowledge  that he is responsible, a person can see his margin of choice. He can choose and act, and choose and act again, without illusion. He can create himself and make himself felt in the world. Such a person has power.”

that he is responsible, a person can see his margin of choice. He can choose and act, and choose and act again, without illusion. He can create himself and make himself felt in the world. Such a person has power.”

Awesome dude.

###

[1] My current fundamental perception of the mechanics of human oppression is found in the referenced column. Also, recognizing how these oppressors like to divide and conquer, the issue of race is very important to me, and I have written on it elsewhere in these columns.

[2] I put quotes around conservative to indicate that the word today, in the era of neoconservatives (who are not conservatives) carries little meaning. I mean conservative in the classical liberal or libertarian sense: small government, economic freedom, personal freedom, peace.

[3] John Taylor Gatto’s magnum opus is The Underground History of American Education. He is a former government school “teacher of the year” in New York who now advocates a complete separation of school and state.

This post has been read 4507 times!