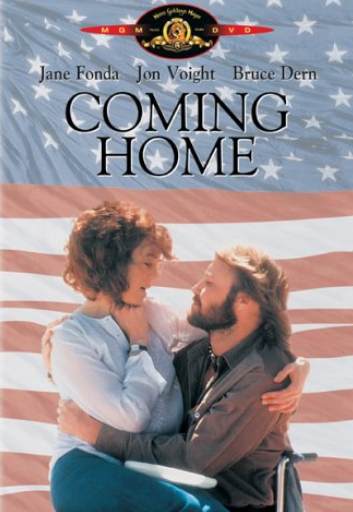

The best all-round antiwar love story of all time (10/10)

Reposted October 11, 2017. Not much has changed. Only now war for most Americans is a bunch of fat cowards sitting in a room murdering women and children with drones. Don’t even need to suit up, just watch TV and push buttons.

Luke Martin (Jon Voight): [Luke’s speech is spliced with final scene of Capt. Bob Hyde where he is at the beach] You know, you want to be a part of it, patriotic, go out and get your licks in for the U.S. of A. And when you get over there, it’s a totally different situation. I mean, you grow up real quick. Because all you’re seeing is, um, a lot of death. And I know some of you guys are going to look at the uniformed man and you’re going to remember all the films and you’re going to think about the glory of other wars and think about some vague patriotic feeling and go off and fight this turkey too. And I’m telling you it ain’t like it’s in the movies. That’s all I want to tell you, because I didn’t have a choice. When I was your age, all I got was some guy standing up like that, man, giving me a lot of bullshit, man, which I caught. I was really in good shape then, man. I was captain of the football team. And I wanted to be a war hero, man, I wanted to go out and kill for my country. And now, I’m here to tell you that I have killed for my country or whatever. And I don’t feel good about it. Because there’s not enough reason, man, to feel a person die in your hands or to see your best buddy get blown away. I’m here to tell you, it’s a lousy thing, man. I don’t see any reason for it. And there’s a lot of shit that I did over there that I [forced with tears] find fucking hard to live with. And I don’t want to see people like you, man, coming back and having to face the rest of your lives with that kind of shit. It’s as simple as that. I don’t feel sorry for myself. I’m a lot fucking smarter now than when I went. And I’m just telling you that there’s a choice to be made here.

Luke Martin (Jon Voight): [Luke’s speech is spliced with final scene of Capt. Bob Hyde where he is at the beach] You know, you want to be a part of it, patriotic, go out and get your licks in for the U.S. of A. And when you get over there, it’s a totally different situation. I mean, you grow up real quick. Because all you’re seeing is, um, a lot of death. And I know some of you guys are going to look at the uniformed man and you’re going to remember all the films and you’re going to think about the glory of other wars and think about some vague patriotic feeling and go off and fight this turkey too. And I’m telling you it ain’t like it’s in the movies. That’s all I want to tell you, because I didn’t have a choice. When I was your age, all I got was some guy standing up like that, man, giving me a lot of bullshit, man, which I caught. I was really in good shape then, man. I was captain of the football team. And I wanted to be a war hero, man, I wanted to go out and kill for my country. And now, I’m here to tell you that I have killed for my country or whatever. And I don’t feel good about it. Because there’s not enough reason, man, to feel a person die in your hands or to see your best buddy get blown away. I’m here to tell you, it’s a lousy thing, man. I don’t see any reason for it. And there’s a lot of shit that I did over there that I [forced with tears] find fucking hard to live with. And I don’t want to see people like you, man, coming back and having to face the rest of your lives with that kind of shit. It’s as simple as that. I don’t feel sorry for myself. I’m a lot fucking smarter now than when I went. And I’m just telling you that there’s a choice to be made here.

Jane Fonda … Sally Hyde

Jon Voight … Luke Martin

Bruce Dern … Capt. Bob Hyde

Penelope Milford … Vi Munson

Robert Carradine … Bill Munson

Robert Ginty … Sgt. Dink Mobley

This ordinary-citizen’s oration from Luke Martin (offered up with an Academy Award winning conviction by Jon Voight) is enough to bury all the pretensions ever generated to support the Universal War Machine. (It just so happens this particular bonecrushing UWM set of cogs is the needless war of my generation, Vietnam.) The rest of the movie gives us a wordless indictment of that war, far more powerful than any grouping of words could ever accomplish.

The story is a marvel of simplicity, centering on a young woman Sally Hyde (Jane Fonda—she also won the Oscar for her role) whose husband Bob Hyde (Bruce Dern) has willingly shipped himself off to the front. Sally is a caring person trying to do the right thing. (Truly, so is Bob, though as a Marine Captain he has a good deal of psychological investment in the righteousness of killing the yellow man.) Sally is more naive about the whys and wherefores that have mired the country into a deepening conflict seemingly light years away from her Southern California digs, both geographically and culturally.

All she knows is her husband is over there and she’s a housewife expected to make the best of it. But eventually Sally—the Hydes have no kids—becomes lonely and bored. She decides to join Vi (Penelope Milford) at the local VA hospital as a volunteer, what we used to call a candy striper. At the hospital we’re introduced to Luke, who has lost the use of his legs due to some shrapnel taken in the back. Luke and Sally went to high school together, where he was the captain of the football team and she was Sally Bender, a cheerleader.

Coming Home is the story of these three “ordinary” Californians trying to reconcile their lives with the horrors of war, as well as with the way injured veterans of that war are shunted into a Purgatory of discarded, disrespected cannon fodder. By covering in so understated a manner the daily rituals of Luke’s fellow wounded at the hospital, the moviemakers compel us to look at how the war has dehumanized all of us. Indeed, we eventually see how even those who were not grossly physically damaged—Bob returns from Nam with a self-inflicted rifle wound for which it is unclear whether it was intentional—are crushed psychologically.

When Bob does return home, or actually when Sally visits him for a week while he’s on leave in Hong Kong, he learns Sally is working at the VA. The period covered is the late 1960s, within a whisker of the launch of the modern women’s movement[1], and a married woman was solely expected to keep house and rear children for her breadwinning mate. He’s upset with her, but more than that, jealous. Yet the conscientious and determined Sally is growing, too, which reminds me of another war movie, Swing Shift, where at least the great human tragedy of war produced an elevation of consciousness in many women.

As in Swing Shift, a deep relationship forms between the wife of the serviceman sent to war and a good man back home—in the case of Coming Home, Luke was in the war just sent home early. Sally quickly sees through Luke’s bitterness and riffs of self-destruction, partly because she genuinely wants to feel needed or useful. After a while, Luke’s resistance breaks down and he shows his like-tenderness toward others: there is an incident where Vi’s shell-shocked brother loses it, a and Luke embraces him while uttering words of encouragement.

Sally begins to fall for him. All she’s known from Bob is “me husband, you Sal.” The chemistry between Luke and Sally builds inexorably, though softly, to a crescendo of lovemaking that quite candidly is the most honestly, enjoyably sensual encounter between a man and woman I’ve ever seen in cinema. Unlike many such scenes—it seems every romantic movie of the 70s inserted an explicit skin-flaunting sexual interlude regardless of plot—this one is critical to the fulfillment of Sally as a person. After the peak, she breathlessly remarks to Luke, “that’s never happened to me before.” I don’t know how Jane accomplished it, but it’s similarly one of the most courageous jobs of acting one is likely to see. Mega kudos, Ms. Fonda. Magical.

Back to the ground, one appreciates how the director included real VA hospital residents of the time, and we even lead into the film with a believable conversation among these real victims—one of them actually supports the war… from sort of a disembodied moral obligation—yet honest. Several visuals are presented of physical therapy juxtaposed with Bob and others running, prepping for going in, or even some war footage. The movie uses appropriately many well-known songs of the era, mainly the Rolling Stones: “Out of Time,” “Just Like a Woman,” “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” “My Girl,” “Good Bye Ruby Tuesday,” “Time.”

Other notables:

Beatles: “Hey Jude,” “Strawberry Fields”

Jefferson Airplane: “White Rabbit”

Buffalo Springfield: “Stop Children What’s That Sound?”

Simon and Garfunkel: “Photograph”

So you can probably figure the plot out now, but I hope I haven’t given away too much of the good stuff. Pretty much it’s all good. Coming Home is an American treasure and an inspiration to anyone looking forward to a world of peace and justice.

###

[1] My sense of when the women’s movement started was with the publication of Betty Friedan’s, The Feminine Mystique, in 1963.

This post has been read 2695 times!