An Illuminating Snippet of 16th Amendment History

By Gregory Sutton [Excerpted from full original article in Lost Horizons here.]

Editor’s Note: The following column appeared recently on the LostHorizons.com site as a Christmas present from its author. Here is the intro from the author on the California Cracking the Code forum:

Editor’s Note: The following column appeared recently on the LostHorizons.com site as a Christmas present from its author. Here is the intro from the author on the California Cracking the Code forum:

Dear Family, Friends, Business Associates, Casual Acquaintances and Libertarian Mentors:

In this time of appreciative giving I wish to share with all of you the precious gift of knowledge. I give this gift with the sole intention of making everyone who has helped make my development as an ardent seeker of freedom, in an otherwise unfree world, more free. In fact if the knowledge that I freely give is actively pursued you may just end up freer that you’d ever imagined you could be. Of course being truly free is not something that is free from effort or achieved by luck alone. But if you build upon the revisionist historical foundation that I give you freely this Christmas your chances of achieving that blissful state of so far unimagined and unrecognized freedom will be vastly improved. I’ll leave it at that other than to hope that however you react to my gift that you all have the best and merriest Christmas’s of all!

The only requirement on your part is to be able to connect to the internet: ANice16thAmendmentSnippet.htm

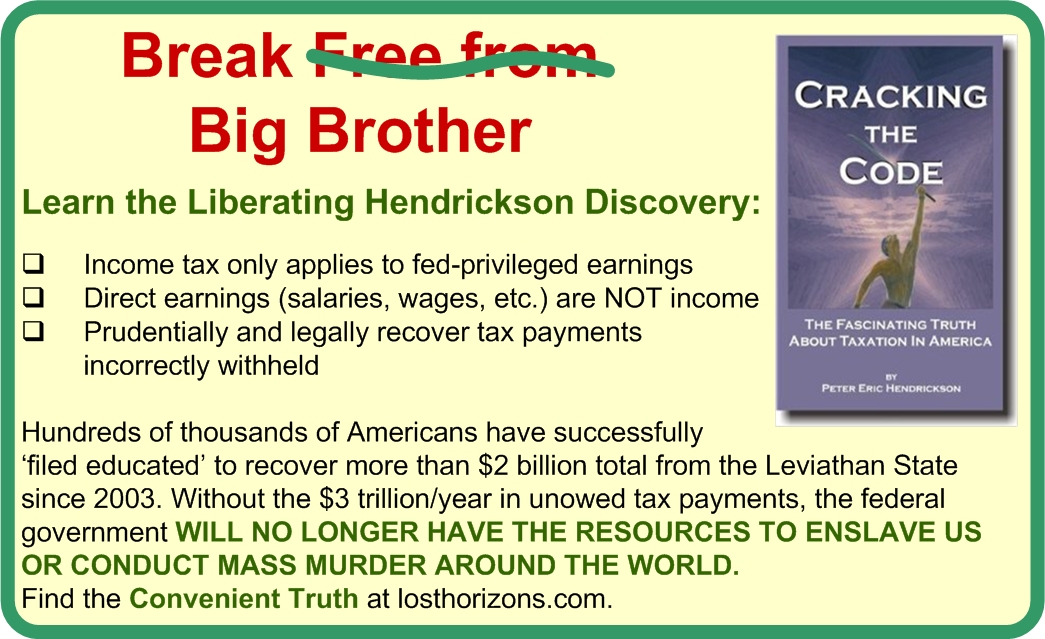

I consider the information in this column by Greg Sutton perhaps the most vital icing on the cake one can imagine of the liberating discovery of Pete Hendrickson in his groundbreaking epic, Cracking the Code: The fascinating truth about taxation in America. Please, please spread this information and Greg’s column on the 16th as if our lives and liberties depend on it. They do. — ed. (brw)

####

IN 1913, AFTER AN EIGHTEEN-YEAR HIATUS, Congress enacted its 20th century revival of the income tax as part of the Revenue Act of 1913. The act became law on October 3 of that year.

The undeservedly maligned and often misunderstood and misrepresented tax was included in the comprehensive revenue legislation package as a result of the 16th Amendment being ratified by the states on February 25, 1913. The Amendment’s intended effect of overturning the Supreme Court’s bare-majority Pollock decision of 1895 had returned to Congress the full palate of taxable privileges that it had originally possessed for revenue purposes before the destructive decision of the Pollock court.

Professor Thomas Powell of Columbia University explained that whole sordid affair succinctly:

“The Pollock Case [1895], with its abandonment of previously well established doctrine, provoked widespread popular criticism. Then followed the movement for the Sixteenth Amendment and its ultimate adoption. The Amendment was very probably widely regarded as in effect a “recall” of the Pollock Case, as the Eleventh Amendment was a recall of Chisholm v. Georgia. … [T]he Income Tax Cases of 1895 were regarded as amendments of what had gone before and that the Sixteenth Amendment was looked upon as a restorative … [and] was a device to repair the damage done to the [unanimous decision] Springer Case [1880] by that bare majority in the Pollock Case.”

Columbia Law Review, 20 Col. L.R. 536 (1920), Prof. Thomas Reed Powell.

The Pollock decision had in effect exempted from the otherwise uniformly applied privilege tax the interest, rent and stock dividends derived from the vast holdings of land granted by Congress to railroad, mining and lumber corporations. The land give-away was one of the means to fulfill the country’s religious like belief in manifest destiny. It began after the southern states had seceded leaving Congress dominated by Henry Clay’s American System proponents. Even with the “Civil War” not going as well as expected and the treasury treacherously diminished, the land give-away started anyway in 1862 with the Pacific Railway Act and continued on unabated by war or economic downturn almost to the turn of the century.

These privileged corporations and their directing officers had properly been subject to the income tax also enacted in 1862 and tested in the Springer case to which Prof. Powell alludes. (William M. Springer had filed a tax return for the year 1865, claiming $50,798 in taxable income with a tax liability of $4,799. Mr. Springer’s claimed taxable income was allegedly from his profession as an attorney at law and the rest from interest on United States bonds. But he refused/neglected to pay the tax because, as he lavishly argued, it was a direct tax enforced without the necessary requirement of apportionment. The unimpressed unanimous Springer court thought otherwise and without equivocation declared the Civil War income tax an excise or privilege tax that had been properly enforced upon an obvious and admitted recipient of taxable income.)

These privileged corporations and their directing officers had properly been subject to the income tax also enacted in 1862 and tested in the Springer case to which Prof. Powell alludes. (William M. Springer had filed a tax return for the year 1865, claiming $50,798 in taxable income with a tax liability of $4,799. Mr. Springer’s claimed taxable income was allegedly from his profession as an attorney at law and the rest from interest on United States bonds. But he refused/neglected to pay the tax because, as he lavishly argued, it was a direct tax enforced without the necessary requirement of apportionment. The unimpressed unanimous Springer court thought otherwise and without equivocation declared the Civil War income tax an excise or privilege tax that had been properly enforced upon an obvious and admitted recipient of taxable income.)

The federal land give-away came to a screeching halt when the corruption-busting Cleveland Democrats swept the House, Senate and Presidency in Grover Cleveland’s lopsided victory for his second nonconsecutive term. The corruption had gotten so bad during the 32 year rule of the “manifest destiny”-crazed Republican party that an anti-corruption revolution was inevitable.

PRESIDENT CLEVELAND was certainly up to the task. Tax reform was one issue at the top of his list. Abuse of the protective tariff by the Republicans had created an enormous political backlash. The people weren’t going to stand for the obvious economic and political inequities that it had produced. It was time for a return to the taxation principles of responsible Constitutional republican government. Those principles were based upon “ability to pay” and “equal distribution of liability” amongst those with ability.

The debates preceding the “radical” Revenue Act of 1894 concentrated on this key issue. Michigan Representative George Richardson: “I favor the income tax because it is asking a contribution of those citizens of the country who have accumulated great wealth and enjoy large incomes by reason of special privileges afforded by legislation,” and Representative Hudson of Kansas: “[T]he majority of the very wealthy are haughty, overbearing, autocratic, mean, and it is that class in particular that the income tax is designed to reach.”

The overwhelming tenor of the times was that the wealthy privilege-beneficiaries should pay because they can pay, and they weren’t paying their fair share with only consumption taxes on the books. So, it was no surprise that an income tax was made a part of the tax reform of 1894 to finally once again tax the beneficiaries of the Republican party’s privilege largesse. It was also no surprise that when the Supreme Court ruled in the Pollock decision that taxable income derived from land granted to railroads, etc. acted as a direct tax upon the property and thus was insulated from the income tax, the people concluded that the court was as corrupt as the previous Republican Congresses had been.

Accordingly, the 1909 Congress, after lengthy debates reminiscent of those of 1894 and with nonpartisan near-unanimous support sent to the states the 16th Amendment for ratification. Early in the ratification process a book written by the popular progressive economist Professor F. C. Howe would be released. Howe revisited the nearly incomprehensible facts surrounding the Congressional land grants recently gathered by a Teddy Roosevelt-commissioned investigation into land-grant corruption. It was estimated that acreage granted directly or indirectly (by giving the land to the states which would then grant it to the railroad corporations) to railroad, mining and lumber corporations was around 300 million acres.

Accordingly, the 1909 Congress, after lengthy debates reminiscent of those of 1894 and with nonpartisan near-unanimous support sent to the states the 16th Amendment for ratification. Early in the ratification process a book written by the popular progressive economist Professor F. C. Howe would be released. Howe revisited the nearly incomprehensible facts surrounding the Congressional land grants recently gathered by a Teddy Roosevelt-commissioned investigation into land-grant corruption. It was estimated that acreage granted directly or indirectly (by giving the land to the states which would then grant it to the railroad corporations) to railroad, mining and lumber corporations was around 300 million acres.

PROFESSOR HOWE’S DEVASTATING EXPOSÉ of what had been going on since the beginning of the Lincoln administration must have been like fingernails on a chalkboard for the privileged elite. For decades these folks had been engaged in disinformation campaigns leveled against the income tax to which they were rightly and lawfully subject.

One of the evasive elites’ favorite disinformation techniques was to flood the American open market of ideas with articles in intellectual journals, by predominately German-educated “experts in political economy,” that described their biased and conflicted conception of the American income tax in elaborate detail. However, each and every single one of these articles intentionally or inadvertently omitted the most important detail: the actual subject of the tax – political privilege. Professor Howe’s book, with the provocative title of Privilege and Democracy In America, helped reestablish in the minds of the people the clear relationship between massive wealth attained and political privilege granted, in graphic detail.

Further, Professor Howe didn’t confine his discussion of political privileges to just the massive Congressional land-grants to a handful of corporations. Another political privilege that had also been obscured by constitutional subterfuge was the protective tariff.

Congress had followed the British practice of perverting the historically-favored practice of raising government revenue with modest and uniform tariffs by raising duties on certain imports to levels which essentially altogether prohibit their importation. The purported goal was to encourage the growth of infant industries by granting to them the privilege of protective market insulation while these domestic producers grew strong enough to compete with European producers.

Congress had followed the British practice of perverting the historically-favored practice of raising government revenue with modest and uniform tariffs by raising duties on certain imports to levels which essentially altogether prohibit their importation. The purported goal was to encourage the growth of infant industries by granting to them the privilege of protective market insulation while these domestic producers grew strong enough to compete with European producers.

But much as in the case of an opioid addict, the seeming necessity for the deployment of the protective privilege (drug) soon became pushed aside by a political and economic addiction to the euphoric profits produced by freezing out competitors and exploiting a captive consumer market. So rather than do what had originally been promised and scale back the privilege of protection once the industries were able to profitably compete with the Europeans, the uncontrollable economic and political dependency created by the privilege dictated instead the prolonging and/or increase of the protection. Eventually tariff rates of 50 or 60 percent or even higher became the norm.

This politically and economically motivated redistribution of the property of the citizenry to the Captains of Industry was accomplished under the guise of a tax measure, but it had nothing to do with the collection of revenue to pay the government’s operating costs. Instead its real purpose and effect was to enormously enrich the domestic producers of the specific commodity targeted by the exorbitant import duty. Just like the privilege of free land, the privilege of market insulation would aggregate untold wealth and power into a few privileged hands.

WITH THE POLITICAL AGITATION created by the constitutional movement to resuscitate the income tax back from the death knell of the Pollock decision and resume taxation of the enormous profits from railroad, mining and lumber privileges, the general, unprivileged public was presented with an opportunity to reign in the abuses and consequences of Congress’s privilege power as exercised in the protective tariff as well. Its interest was further compelled by the prospect of lower prices on domestically produced commodities by the proposed reduction of rates or elimination altogether of protective tariffs on imported goods.

In addition, the American people were also enticed by the prospect of lower excise rates on commodities sold internally. All of these promises of reductions of taxes which directly affected the American public were justified as fiscally prudent, because the reestablishment of an income tax on privileged wealth was to make up, plus some, the deficit created by the reductions. It is therefore easy to understand why the several states had eventually ratified the 16th Amendment because it was a win-win for the states and their citizens. That the federal government had finally figured out a way to partially if not wholly finance itself by taxing its own privileged activities was a wish come true for those that sought to maintain a balance of power that favored the states, leaving to the states the taxation of its own citizens as they deemed fit and proper. Think locally, act locally.

In addition, the American people were also enticed by the prospect of lower excise rates on commodities sold internally. All of these promises of reductions of taxes which directly affected the American public were justified as fiscally prudent, because the reestablishment of an income tax on privileged wealth was to make up, plus some, the deficit created by the reductions. It is therefore easy to understand why the several states had eventually ratified the 16th Amendment because it was a win-win for the states and their citizens. That the federal government had finally figured out a way to partially if not wholly finance itself by taxing its own privileged activities was a wish come true for those that sought to maintain a balance of power that favored the states, leaving to the states the taxation of its own citizens as they deemed fit and proper. Think locally, act locally.

IN CONFIDENT EXUBERANCE, Congressional lawmakers established March 1 (or the next business day after, if that date fell on a Sunday, as it did in 1914) as the filing deadline from this point forward in time. That gave the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) — and taxpayers (that is, those who engage in taxable privileged activities) — only five months to get ready for the inaugural filing season. Was Congress too unrealistically optimistic that the BIR and the taxpayers subject to the tax would be prepared to enforce the new century’s income tax on such short notice?

If one were to read the large, national newspapers of the day one might conclude such a thing. But one must keep in mind that these large national news organizations had been bought up or otherwise controlled many years earlier by these very corporations and individuals that were now going to be the subject of the resurrected income tax. It was obviously not in the best interests of these privileged elite for the news organs that they controlled to wax eloquently on the virtues of an income tax.

Not only would such truthful coverage of the income tax uncomfortably reiterate the actual subject of the tax as privileged activities granted to them by the federal government (which are measured by the taxable income that they produce), but such humdrum truthful coverage would lack the sensational appeal and impact that sells newspapers. Thus we see in the historical record that nearly all reporting by newspapers on the 1913 income tax was done from the perspective that the government in its zeal to tax incomes had failed miserably to take into consideration the imagined myriad of picayunish details of enforcement. The denigration of the federal government was a popular and sensational subject which sold newspapers and it evidently worked effectively in their coverage of the 1913 income tax.

So, despite what the newspapers of that time were sensationalizing, Congress’s alleged over-confidence in the executive department’s ability to enforce the tax smoothly and efficiently was mostly a cover for their intentional neglect to discuss the subject of the tax. The 16th Amendment had been ratified a full year before the March 2, 1914 filing date. The amendment’s ratification gave notice to those engaged in taxable privileges that it was the intent of Congress to tax their activities from that moment forward, no matter when it might become statutorily official.

In the same vein, the BIR also had proper notice that it had better start compiling a taxable privileged activities assessment roll, if it didn’t already have one prepared, again, no matter when the tax might become a statutory reality. So, even before Congress got around to putting an income tax in the statute books, it is not unreasonable to assume that the BIR and the subject taxpayers were essentially already prepared for when Congress actually got around to making it a statutory reality on Oct. 3, 1913. The only thing left for Congress to actually determine by statute were the variables needed to compute the amount of tax due, such as the rate of tax, the exemption threshold, allowable deductions and, of course, the filing deadline.

BUT THE REASONABLE ASSUMPTION OF CONGRESS that everything would go smoothly, considering the income tax’s benign and in-house nature, encountered a few unexpected hiccups. As briefly mentioned earlier, the last two decades of the 19th century saw an influx of German-educated intellectuals and “experts” who lacked any understanding of the principles and practices of privilege taxation, or at least behaved as though this were true. These darlings of the emerging progressive “expert” class would publish their gibberish about the income tax in intellectual journals that were the popular rage of the time. The influence that these foreign educated political economists had on the national press, the young minds matriculating in American universities where these “experts” were plying their trade (one such victim, Frank Chodorov, comes to mind), and the few autodidacts of the population that were digesting these intellectual journals was grossly underestimated by Congress.

The “fake news” that these “experts” were peddling: that the purpose of the 16th Amendment was to allow a direct income tax without apportionment, must have surprisingly had a much greater influence on a public that historically should have known better. What occurred as a result of the widespread dissemination of this “fake news” was that, beginning with the income tax legislation of Oct. 3, 1913, the BIR and representatives and senators in Congress were besieged with letters inquiring as to a private sector citizens’ responsibility under the law as written.

The Treasury Department attempted a quick fix by issuing a formal public announcement in answer to the flurry of inquiries. The announcement directed those that anticipated they had a filing requirement to file their return showing the alleged quantity of tax due by March 2, 1914 (again, March 1, was a Sunday), but to not send in payment with the return. Instead, each taxpayer’s 1040 form was to be first reviewed by the local collector of internal revenue and then forwarded to Washington for a second review at BIR headquarters. After the return’s accuracy or inaccuracy was established, collectors were required to submit a bill to actual taxpayers by June 1. Final payment was due by June 30.

Many are perplexed by this action of the Treasury Department. But this is only because they fail to recognize that the Federal government has foreknowledge of the privileged activities that it grants and for which it is thereafter administratively responsible.

What we might think of as the “privileged activities assessment roll” is merely the list of all federally generated privileges (sources of taxable income) and their willing recipients (taxpayers). Doubtless such a schedule would be maintained whether Congress has made privileged activities taxable (via an income tax) or not. By comparing all returns filed to the official “privileged activities assessment roll,” those returns that had been sent in erroneously, as a result of “fake news”, could be easily weeded out merely by not sending the propagandized filers a subsequent bill.

ANOTHER ONE OF THE MANY IMAGINED ISSUES at this time in income tax history was that of evasion. Many writers then and today claim that the exceedingly low filing rate (as compared to what they imagined it should have been) was a result of gross and uncontested evasion. But nothing could be further from the truth.

One of the chief virtues of an income tax amongst the various revenue sources utilized by Congress is that its nature as a privilege tax precludes the threat of evasion. If the federal government has foreknowledge of an individual’s exercise of privileged activities and the individual is duly and thoughtfully made aware that the federal government knows of his activities, only a privileged moron like William M. Springer would attempt to evade the tax.

REVEALING OF THE MAJOR MEDIA’S understanding of the income tax as an excise or privilege tax at its revival in 1913 was the otherwise sensationalized news reporting done by the large national newspapers of the country. This reporting inadvertently explained by implication what the papers weren’t openly acknowledging.

As the filing date of March 2 approached reporters across the land and even abroad sought interviews with taxpayers to report on the progress, good or bad, of the filing process. Did these reporters seek out well-to-do individuals in the private sector who’s earnings would presumably easily surpass the minimum threshold filing requirement? Not a one that I could find.

No interviews with a reporter’s wife’s filthy rich Aunt Edith. No interviews with the owner of a reporter’s favorite fancy and expensive restaurant.

Reflecting understanding of the tax as an excise, it is only officers and employees of the federal government that were interviewed, sparing the reporters having to guess if any private-sector individual, no matter how wealthy he was, had taxable income. These reporters knew that every bit of a federal employee’s or officer’s pay, salary or wages was taxable income, while that of most other people’s was not, and they acted accordingly.

A New York Times reporter in Paris hooked up with the US consul general, Alexander M. Thackara, in early February and inquired as to his readiness for the upcoming filing deadline, by asking if he had the necessary 1040 form to complete the task. Mr. Consul General Thackara was clueless. “Blank 1040: what is that? I never saw one,” he told the reporter.

It seems the BIR was slow to get forms to the embassies and consulates around the globe. Mr. Thackara soon realized the dire consequences of his ignorance and the BIR’s tardiness. “I want one quick,” he said. “I am a government employee, so it is simply out of the question for me to be a single day late in filing my blank [Form 1040].”

The Los Angeles Times sought out, of all the taxable people available, John P. Carter, Collector of Internal Revenue, at the Federal Building in Los Angeles. It was reported that “he writhed in his chair” due to the complexity involved in filling out his form 1040.

The story went on that he had “an expression of anguish on his face as he labored over the income tax return he is to make to himself as John P. Carter, Collector of Internal Revenue.” Another taxable individual queried was Alvey A. Adee, second assistant secretary of state. It was reported that he was “stumped”. He told reporters: “To be perfectly frank, I feel a good bit puzzled.”

THERE ARE OTHER INSTANCES where the news articles give in to the fact that the federal government possesses foreknowledge of the amount of taxpayers within a district liable for the income tax…

[For full remarkable article please consult original link by Greg Sutton.]

This revisionist look at the income tax of 1913 applies just as accurately to the “Civil War” income tax, the 1894 income tax and the continuous use of the tax after 1913 to date. It is an excise upon federally granted privileges and is measured by the income received as a result of the willful exercise of all privileges (from whatever source derived) that Congress supposedly conjures up as allowed by the Constitution. With the current modeling-clay view of the Constitution expect new and novel privileges to appear, such as ACA, by which Congress may well have meant to broaden the very narrow “taxpayer” base of the income tax.

***

Greg Sutton is a business owner, legal scholar and all around good guy. Greg makes his home in Northern California and on many chat rooms, newsgroups and commenting platforms throughout cyberspace. Greg’s trenchant analysis of the ancient English “Office Duty” as a model for certain key aspects of the American income tax can be found here.

This post has been read 1409 times!