Powerful humanitarian film in a challenging time

Ma Joad: You’re not aimin’ to kill nobody.

Ma Joad: You’re not aimin’ to kill nobody.

Tom Joad: No, Ma, not that. That ain’t it. It’s just, well as long as I’m an outlaw anyways… maybe I can do somethin’… maybe I can just find out somethin’, just scrounge around and maybe find out what it is that’s wrong and see if they ain’t somethin’ that can be done about it. I ain’t thought it out all clear, Ma. I can’t. I don’t know enough.

Ma Joad: How am I gonna know about ya, Tommy? Why they could kill ya and I’d never know.

Tom Joad: Well, maybe it’s like Casy says. A fellow ain’t got a soul of his own, just little piece of a big soul, the one big soul that belongs to everybody, then…

Ma Joad: Then what, Tom?

Tom Joad: Then it don’t matter. I’ll be all around in the dark—I’ll be everywhere. Wherever you can look—wherever there’s a fight, so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever there’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there. I’ll be in the way guys yell when they’re mad. I’ll be in the way kids laugh when they’re hungry and they know supper’s ready, and when the people are eatin’ the stuff they raise and livin’ in the houses they build—I’ll be there, too.

Spoken like a true Free Stater! It’s funny how a novelist (John Steinbeck in his Grapes of Wrath) can express in a single scene about the human condition volumes of an ideologue’s reasoning. While teenaging as a Goldwater conservative, I continued to miss and dismiss the movie The Grapes of Wrath; as a young right-wing, corporate ‘libertarian,’ I said to myself, “Steinbeck and his ilk are a bunch of commies. They want to take away everything the lawyers, bankers, landowners, and politicians have poured their sweat and blood into… hand it to a bunch of welfare chiselers.”

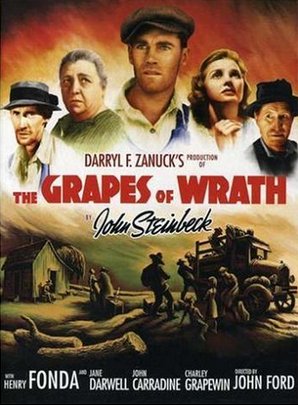

Henry Fonda … Tom Joad

Jane Darwell … Ma Joad

John Carradine … Casy

Charley Grapewin … Grandpa

Dorris Bowdon … Rosasharn

Russell Simpson … Pa Joad

But back to the book and movie, Tom Joad (Henry Fonda) comes from a sharecropper’s family in Oklahoma. He’s done time for being in a fight where his opponent dies. He returns to the farm in the Dust Bowl era only to find everyone packed up and gone, part of a mass migration to California where supposedly plenty of farm jobs exist for them. Tom catches up with his family before the authorities come to demolish the home where they’re staying[1] and about ten of them head west in a big ol’ beat up truck that reminds you of the Beverly Hillbillies.

The story is how human beings, when faced with natural disaster and social structures that systematically destroy their ability to earn a living, press on with dignity and hope. [Hmmm, seems applicable to the world of our Wall-Street takeover, eh?] Indeed, I see the movie (and book) as one long song to the indomitability of the human spirit. No, these aren’t Randian nonfamilial, hyperindividualistic characters seeking to achieve prodigious engineering feats against all odds. Instead, they’re about family, indeed, Wrath is the ultimate family-value movie… the ultimate family value being survival.

The Californians, not to mention other state denizens along the way, are depicted as generally hostile to the Okies, and opportunistic. When the Joads first arrive, we don’t see much in the way of Red Cross or Salvation Army food lines. Rather, several helter skelter tent cities built around junk yards without running water or systems of self-governance. The local yokels—cops and their redneck-cretin bullies—come in to the camps throw their weight around, ostensibly looking for Bolshevik troublemakers. I’m watching a scene where the pigsters attempt to arbitrarily detain a man for insisting on a seeing a contract, and it makes me think of modern, routine, everyday American federal/state Homeland-Secirity, Border-Patrol, drug-war, police-state practices.

Some things never change.

But the corporate farms strong-arm the sudden influx of tens of thousands of desperate poor people into what amounts to slave labor. The wages are driven so low, the families cannot get enough to eat. No attempt is made by the authorities to arrange for humane accommodation until or unless satisfactory work can be obtained. With the exception of a diffusely conceived WPA[2]-like facility toward the end of the story. [Just as one doesn’t need to see socialism as a solution to healthcare problems to appreciate their tragic dimensions, the obvious inhumanity of the Okies’ situation is enough to make one reconsider the privileged, ruling-class methods by which land and other resources are owned, controlled, and used.[3]]

But enough of the political angle. What makes the story of the Joads resonate is how they keep together, exercise family values in extremis, and—through the words of Tom Joad above—reach a degree of spiritual enlightenment in adversity. Further, as a movie that won Oscars (1940) for best director and Ma Joad’s (Jane Darwell’s) performance, the superlative craft behind it is manifest. It’s getting easier for me to watch the old movies: it’s all about story and ideas and how they’re conveyed. Who cares about stage sets and spliced-in location footage?

When Henry Fonda—he was nominated for Best Actor, but that year the Oscar went to Jimmy Stewart for The Philadelphia Story)—looks everyone in the eye, talks straight about right and wrong, expresses his hopes and misgivings… well, I see an effective early prototype for the method acting anti-heroes soon to come with Brando, McQueen, DeNiro, and so on. You also appreciate the brutal honesty of the settings, which weren’t quite so frank as the book but still revolutionary for Hollywood in those days. Not to mention the ideas embedded. Steinbeck was a compassionate American who saw major flaws in the corporatist system; he certainly was not a Bolshevik or Communist, and did not even wish to be known as a social crusader… only a good writer casting a discerning, realistic lens on a troubling subject.

Great book, great film. You will be (re)impressed.

###

[1] That situation, where the land owners remove the land users, reveals the classic issue of humane and just distribution of property rights.

[2] Works Progress Administration

[3] There are a number of freedom people who endorse “Georgist” concepts of equality of distribution and access to natural resources such as land for those willing to mix their labor therein (forgive my loose definition, but the movement seems yet small and I haven’t looked into the subject much; I will). These are known as geolibertarians, and here’s a Website, from which the following description is drawn:

“We Geolibertarians distinguish ourselves from right-wing, “royal” libertarians by our profound respect for the principle that one has private property in the fruits of one’s labor. This includes the fruits of mental labor and the results of reinvestment of legitimate private property (capital) in future production. We remain consistent in that respect by recognizing, as did the classic liberals, that land and raw natural resources are not the fruits of labor, but a common heritage to be accessed on terms that are equal under the law for everyone. The statist system of land tenure empowers non-producing landlords to extract the fruits of tenants’ labor.”

This post has been read 2923 times!

I see you don’t monetize your page, don’t waste your traffic, you can earn additional bucks every month because you’ve got high quality content.

If you want to know how to make extra money, search for:

Mertiso’s tips best adsense alternative