Magic classic with unforgettable performances 8.5/10

They told us your splendid victories, but not of the price you paid. — Emma Hamilton

They told us your splendid victories, but not of the price you paid. — Emma Hamilton

Whoever came up with the idea of Turner Classic Movies—well, it was Ted Turner with the help of Robert Osborne and Carrie Fisher, of course—should have a statue or a movie studio named after him. Readers may recall a couple of other occasions when my movie-of-the-week review hailed back to a simpler time when cinema was a more straightforward theatrical presentation and a bag of popcorn, even adjusted for inflation, cost somewhere around a nickel (with no refills). Follow the Fleet and Seven Men from Now are two such reviews that came on the heels of my presence at Mom’s while the dial was turned to TCM. In both cases I was pleasantly surprised an old flick could be so good without being Casablanca.

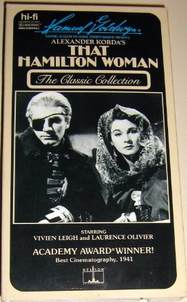

And that same sort of pleasant surprise just happened the other day with That Hamilton Woman, starring Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh—though for different reasons. In fact, the main attraction for me about this film is twofold: a) the magic of the actors and b) the unforced romanticism of the cinematic effort.

Vivien Leigh … Emma Lady Hamilton

Laurence Olivier … Lord Horatio Nelson

Alan Mowbray … Sir William Hamilton

Sara Allgood … Mrs. Cadogan-Lyon

Gladys Cooper … Lady Frances Nelson

Henry Wilcoxon … Captain Hardy

I probably don’t have to explain that romanticism in art, especially literature and movies, has less to do with romantic love than with heroic conceptions of humanity. That Hamilton Woman appeals to this romanticism that was more typical of the movies of the time (1941); we’ve tended to diminish romantic movies, particularly where the heroes fight valiantly for a political cause. For example, it’s always astounded me that the American War for Independence did not inspire more romantic creations in the movie industry. Perhaps the century of state slaughter—well more than 100 million people were killed by governments during the 20th century—with its irrational collectivizing philosophies of all flavors put a damper on classic heroics.

Nevertheless, in the time of Lord Nelson and Lady Hamilton (roughly the end of the 18th century), or at least in 1940s-Hollywood treatment of their adventures, the ideas of general liberty carried a certain cachet. Throughout the movie—and I’m certain this is partly because we, the viewers at the time, were on the threshold of WW2—Admiral Horatio Nelson (Laurence Olivier) refers to Napoleon as a dictator who is an enemy of everyman’s freedom.

Further, Lord Nelson feels and argues on several occasions that the British Fleet, the British in general, should not shirk from their role as guarantors of world liberty. The sense of libertarian responsibility rings true for the time, indeed, it tends to bring out a little of the Anglophile in me. I’m thinking the Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights, and all those things that make America America are in fact derived from some British (well Scottish, e.g. John Locke) conceptions of the rights of man. And let’s not forget the Magna Carta… not to mention I’m sure several other humanitarian points of English history that I never learned much about.

History is full of ironies. Consider the pre-Napoleonic French were allies of the American revolutionaries, and we can see that England of the time of the War for Independence had turned imperialistic —no doubt against the arguments of some (classical) liberals who maintained much as modern libertarians do that their country was meant to be a republic not an empire.

The sense of pride of country also reminds me of Master and Commander, another English seafaring-based tale. It’s rather stirring in both cases when the characters exclaim on the importance of their missions to decent folk everywhere who yearn to breathe free. We feel that passion and pride in the person of Lord Nelson when he storms into the port of Naples, Italy, requesting the help of British Ambassador Sir William Hamilton (Alan Mowbray). It’s urgent and requires the intervention of the Italian king, but the bureaucracy is such an impediment that the authorization will take days. Enter Lady Emma Hamilton (Vivien Leigh)—hubba hubba—who is in daily contact with the queen. She will help the admiral get what he needs that very day.

So the Lord and the Lady meet, and right away you see how this is going to become an affair to remember, a love for all time. And it’s at this moment as I’m watching the movie—I really have seen very little of Laurence Olivier’s work, yet I recognize Vivien Leigh from her Academy Award winning performances in Gone With the Wind (1939) and A Streetcar Named Desire (1951)—I realize these two are very special stars in the thespian galaxy.

In our modern cinema—even via home-based DVDs—we’ve become accustomed to views of handheld cameras and intimate sounds from sophisticated recording techniques. Modern film actors do not need to project their voices and persons nearly so much as once was the case. When That Hamilton Woman was made in 1941, many film actors also performed a lot of work on stage, as did Olivier and Leigh. So when you watch this movie and witness these actors going through their paces, it strikes you how powerfully they inhabit their characters; I mean Olivier is Nelson and Leigh is Lady Hamilton. I feel their performances capture, as much as possible in film, the incredible presence one can experience in a stage play.

It’s strange to recount: I, who had never really watched much of either of these great actors, felt a special magic, truly I did. Olivier has an athletic regal bearing; he portrays Horatio Nelson, one of the greatest military strategists, tacticians, and commanders of all time, with strength and passion. You can sense his integrity a mile away; you can also see his depth of feeling for Emma Hamilton, whom Vivien Leigh plays with a seductive level of charm. Remember her role as Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind? That gives you some idea. Rhett Butler claimed Scarlett was the most charming woman he’d ever met—other women being more beautiful or intelligent. The young Emma is equally full of life, and quick and bright, becoming increasingly sensitive to the cares of this great man with a broken wing and a caring side.

Vivien Leigh, actually, is considered one of the most physically beautiful actresses ever. But she’s so light on her stage feet, she floats like a butterfly among the flowers. Also, check out the Wikipedia on Lady Hamilton; life imitates art, as you can see the real Lady Hamilton is also one of the more beautiful women of her time.

The plot is based on real events. Lord Nelson and Lady Hamilton fall in love, she becomes his mistress, yet neither Nelson nor Ambassador Hamilton divorce their respective spouses. It created quite a stir in its time, as extramarital affairs were rare at that level, especially when the couple were publicly committed to each other and in fact lived together. It’s a treat to watch the actors breathe life into such a challenging relationship. And you realize that good movies are not about the scenery or special effects, not about the sets—the battleships hook horns in some kind of glorified bathtub—but about the people doing the work. And the plot. Three and a half stars.

This post has been read 1521 times!

Point taken, in fact, I’ve come to regard the British Empire–the ones actually engaged at it from the top–to be perhaps the most noxious in history. Hard to make an objective rating system, isn’t it?

Maybe three years ago I came to know that the Brits committed horrendous atrocities on American Patriot prisoners and regular civilians who refused to swear loyalty to the Crown, causing about 10,000 deaths on the HMS Jersey prison barge in New York Harbor alone (compared to roughly 4,000 battle deaths for the colonials). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Jersey_%281736%29. The depredations of the British Imperialists on other countries–Ireland, Scotland, Australia, etc.–are equally horrific. Though the current American Empire is vying not to be outdone.

I can see we are split in our “admiration” of the British. I always admired the French, Irish and what is now Germany and Austrian libertarians. Then there is the Polish colonel (general in his own country) who lead troops during Revolutionary War battles and gave his entire fortune to the freeing of slaves, realizing the slavery, promoted by the British, is evil.

The same way I admire legal systems built upon common sense rather than precedent.

As far as “guarantors of freedom”, for the people on the other side it was imperialism. So many people killed, imprisoned and displaced. So many historical monuments looted, eg. pyramids, Grecian, African, Indian. Heavy use of slavery in its most barbaric terms. Judge them by their deeds; not their puffery.

They cut down on the cannibalism along the Pacific Ocean islands but only after throwing out the Portuguese, who were the first to supplant the local cuisine with European ideas.